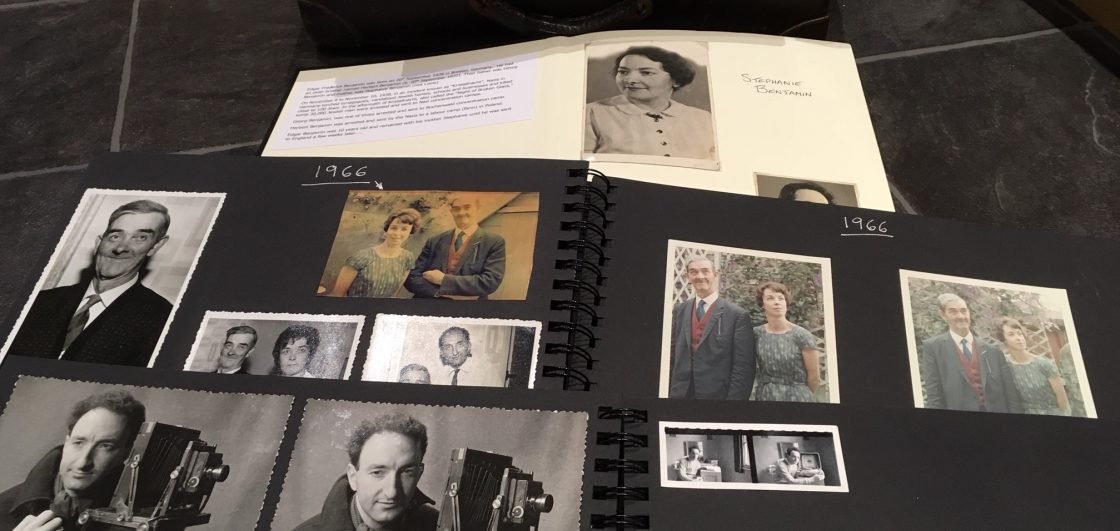

My Grandmother, Stephanie (Steffi) Löw, was born on 27th Aug 1895 in Přerov, Moravia-Silesia, Czechoslovakia (now known as the Czech Republic). Přerov is a town on the Bečva river in the Olomouc Region.

Her father was Sigmund Löw, a locomotive driver at the Northern Railway in Přerov, and her mother was Johanna Löw (née Wellner).

She married Georg Benjamin on 2nd Mar 1922 in Breslau, Germany and later that year gave birth to their first son, Herbert Siegesmund Benjamin on 20th Sep 1922.

Six years later (to the day) Stephanie and Georg had their second son, Edgar Fritz Benjamin, who was born 20th Sep 1928 in Breslau, Germany.

They lived a happy life in Breslau, living close to their extended family but their happiness was short-lived.

The Nazi Rise to Power

In July 1932 Hitler spoke in Breslau, attracting 16,000 listeners. In the following elections his party received 43% of the Breslau vote, the third-highest result in Germany. On 30th January 1933 he was appointed Chancellor of Germany.

It was not long before Jewish businessmen were forced to sell their businesses to “Aryans” (non-Jews) and attacks and harassment of Jewish professionals in Breslau were both horrific and routine. The city was notorious for its enthusiastic participation in anti-Jewish actions from 1933 onwards and many people died as a consequence. Nazism had now made anti-Semitism socially acceptable in Germany. Jews had to surrender their passports so that their validity outside Germany was nullified. Jews were being blamed for inflation and even one newspaper claimed that “all our misfortunes are the fault of the Jews”.

The implementation of the Nuremberg laws in September 1935 meant that Jews became total outcasts of society. In November 1935 Jews were deprived of their German citizenship and in 1938 were forbidden to drive and required to return their licenses.

Many Jews throughout Germany sought to emigrate, although there was still a large proportion of German Jews who were initially determined to stay in their homeland and thought this current wave of anti-Semitism would pass.

As the years went on it became evident that this was not the case but it also became more difficult for families to emigrate. Stephanie’s husband Georg had fought for Germany during the first world war and had been awarded the Iron Cross for his bravery but this now counted for nothing.

The Breslau Jews maintained a stance of defiance and sought to persevere as a cohesive group with its own institutions. They categorically denied the Nazi claim that they were not genuine Germans, but at the same time they also refused to abandon their Jewish heritage. They created a new school for the children evicted from public schools, established a variety of new cultural institutions, placed new emphasis on religious observance, maintained the Jewish hospital against all odds, and, perhaps most remarkably, increased the range of welfare services, which were desperately needed as more and more of their number lost their livelihood. In short, the Jews of Breslau refused to abandon either their institutions or the values that they had nurtured for decades.

That was the heart of the problem of German Jewry: It was so much a part of German society that the Nazi blow hit it from within. Until 1938 many German Jews never thought of leaving Germany.

Kristallnacht

Between November 9th and November 10th 1938 an incident known as “Kristallnacht” (also called the “Night of Broken Glass”) took place across Germany.

German Jews had been subjected to repressive policies since 1933, when Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) became chancellor of Germany. However, prior to Kristallnacht, these Nazi policies had been primarily non-violent.

Nazi Party officials, members of the SA and the Hitler Youth carried out a wave of violent anti-Jewish pogroms throughout Germany. The rioters attacked Jewish residents and their homes. Jewish-owned shops and businesses were also plundered. They destroyed hundreds of synagogues, many of them burned in full view of firefighters and the German public and looted more than 7,000 Jewish-owned businesses and other commercial establishments. Jewish cemeteries were desecrated in many regions. Almost 100 Jewish residents in Germany lost their lives in the violence. In the following weeks the German government created new laws and decrees designed specifically to deprive Jews of their property and of their means of livelihood even as the intensification of government persecution sought to force Jews from public life and force their emigration from the country.

Thus, Kristallnacht figures as an essential turning point in Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews, which culminated in the Holocaust, the attempt to annihilate European Jews during the war.

Arrests

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, some 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps. Stephanie’s husband, Georg, was one of those arrested and was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp on November 12th, 1938. The inmates were assaulted and intimidated in these camps and were instructed to leave Germany on their release. He remained in the camp until his release on December 2nd 1938.

During her husband’s imprisonment, Stephanie was desperately trying to find a route out of Germany for her youngest son Edgar who had just turned 10 years old.

The Kindertransport

Fortunately, a program called ‘Kindertransport’ was created.

The Kindertransport (Children Transport) started directly after Kristallnacht and was a process where children under 18 would be transported to safety in other countries. The aim was for them to be taken in by foster families or relatives until they could be returned to their parents at the end of the war. The majority of the children did not see their families again, as they were victims of the Holocaust. It was largely financed by the Refugee Children’s Movement and the Central British Fund for German Jewry.

Stephanie applied for a place for Edgar on the Kindertransport and fortunately he left Germany on the first Kindertransport evacuation. The organization generally favoured children whose emigration was urgent because their parents were in concentration camps or were no longer able to support them.

The first transport arrived three weeks after Kristallnacht in Harwich, Great Britain, on December 2nd 1938 with nearly 200 children on board. Edgar’s father, Georg, was held in Buchenwald Camp until 2nd December 1938 – the same date that Edgar arrived in England. Edgar had not seen his father since his imprisonment in Buchenwald.

It must have been very traumatic for Stephanie to send Edgar away into the “unknown” and for an uncertain time. She would have had the incredible task of saying goodbye to her 10-year-old son Edgar.

One can only assume that she promised Edgar that she and his father would join him as soon as possible. There are many records of tears and screaming at the various train-stations where the actual parting took place. Even older children, more willing to accept the parent(s) ‘explanation’, would at some point realise that he or she would be separated from his or her parents for a long and indefinite time. That final departure was the last time that Stephanie saw her son Edgar.

Her husband Georg had been ordered to leave the country after his release from the concentration camp in December 1938 and was fortunate to be accepted at Kitchener Camp in England. One suspects Georg left Germany with the intention of getting his wife Stefanie out but then could not. One major impediment, that would not have been predictable in advance, was when the War would begin. When Georg left Germany on 25th July 1939 there would have only been weeks before war was declared. The declaration of war closed all official escape routes out of Germany ending all hopes of being reunited with loved ones, at least for the foreseeable future.

Alone in Nazi Germany

Stephanie was now without her immediate family and conditions for German Jews grew increasingly worse. Unfortunately, Stephanie had been unable to leave Breslau as she couldn’t get a visa to any other country. There was also a financial issue by this stage. Families had had to pay huge sums of money to get their husbands and sons out of the camps after the incarcerations that followed the November 1938 pogroms. Most Jewish families would have been losing their businesses and jobs over the preceding six years since the National Socialists came to power in 1933. Jews had even been forced to pay for the repairs required to towns and cities after the pogroms.

In the summer of 1940, Jews were ordered to surrender all telephones in their homes. In December 1941 Jews were even denied access to public telephones. At about this time Jews also had to surrender their bicycles, cameras and vacuum cleaners. They could only shop at designated hours and their ration cards, stamped “Jude”, limited the amounts and kinds of food they could buy; shopkeepers were not to sell them any fish or eggs. In addition, Jewish use of electricity was restricted to 40 kilowatts per month.

As of late 1941, trams could only be used by Jews to get to work and then only if the distance was more than 4 kilometres. They were not entitled to sit down in the cars or on the platform, where they were obliged to display special yellow identity cards. All men between sixteen and sixty and all women between sixteen and fifty-five had to register for work and if a Jewish doctor pronounced them fit, they were assigned the most menial tasks such as sorting papers, rags, fragments and garbage. Most of these jobs were located in the suburbs or outskirts of the city, forcing the workers to spend 30% of their daily wage of 1 Mark on transportation.

No Escape

Survival for German Jews would often have been an issue of class in the end – If you had cash or connections, getting out of Germany wasn’t a problem but for those without prospects, money, or relatives abroad the doors to other countries were firmly shut.

There is very little information on Stephanie’s day to day activities between 1939 and her deportation in 1941. Many Jews continued to look for means of escape from Germany but Stephanie was unable to find a way out. By now the UK had set age limits on accepting Jews for asylum and at the age of 46 she would have been refused on the grounds that she ‘was too old’.

Her place of residence in Breslau may have also changed due to her now being on her own and by September 1941, the remaining Jews were moved into designated “Jewish houses.” It is doubtful there would have been any communication between Stephanie and her husband Georg from him leaving Germany in July 1939 as the war started only weeks later in September 1939.

Deportation

Stephanie was deported in November 1941 and witness testimonies from this time show that many of the remaining Jews in Breslau received notice around 15th November 1941 that they had to vacate their dwellings. Everyone knew that this meant ‘relocation’. They believed they were being sent for resettlement in the East and received a list of items deemed necessary for their new life. They were asked to wear two sets of clothing and to bring tools, sewing machines and provisions for 8-10 days and as much luggage as they could carry.

In the early hours of 21st November 1941, earlier than expected, Stephanie was picked up by the Gestapo and along with about a thousand other Breslau Jews was escorted to the Schiesswerderplatz where an unused concert hall in the vicinity of the Ordertor train station served as an assembly site.

The deportees were forced to remain here for four days while the Gestapo recorded and catalogued their assets and to authorise the seizure of these assets by the German Reich. The documents below dated 21 November 1941 show that Stephanie’s assets were recorded and confiscated that day.

The despair must have been overwhelming for many people in this assembly point and reports state that many people took their own lives during these few days.

On November 25th 1941 they were led to the nearby Odertor railway station where a train was waiting for them. They were taken by train, along with thousands of other German and Austrian Jews, to Kaunas, in what is now Lithuania. The journey would have taken approximately 3 days via Posen (Poznan) and Insterburg (Chernyakhovsk) in Eastern Prussia to Kaunas.

Execution

From the train, they were marched 6km along the Ghetto Fence to a hilltop overlooking the city and held in a courtyard at the Ninth Fort, one of a series of fixed fortifications surrounding the city. Their belongings were kept at the railway station and were later appropriated by the local German authorities. They were held here for one night and the next morning were herded in large groups to a field above the fort. The Gestapo men and the Lithuanians ordered the people to line up in a row, in groups of 80 persons. They were forced to undress and line up next to huge pits before being shot down by SS-men and Lithuanians lying in wait for them with machine guns set up on the wooded hill by the graves. At the same time, truck engines were revved up to drown out the gun fire and screams.

On 29 November, 1941, my grandmother, Stephanie Benjamin was shot here, in this field, by members of the Nazi death squad Einsatzkommando 3, under the command of a Swiss-born SS colonel called Karl Jäger. On that one day alone, they murdered 2,000 Jews, including 150 children who had been deported by train from Vienna and from my grandmother’s town of Breslau.

There is a photograph in the Ninth Fort museum showing Jews from Munich before their deportation to Kaunas, just a few days before my grandmother was deported from Breslau. Many of the women are shown elegantly dressed, some in fur coats.

Three days after she was shot, SS Colonel Karl Jäger submitted a report to his superiors, listing in meticulous detail the number of Jews he had ordered to be killed each day over the previous six months. That’s how I know so exactly my grandmother’s fate: it’s there, in black and white:

“29.11.41 693 Jewish men, 1,155 Jewish women, 152 Jewish children (evacuated from Vienna and Breslau).”

The original document in German can be read here .

Karl Jäger managed to escape capture at the end of the war, but was eventually arrested in 1959. He hanged himself while awaiting trial.

A Jewish child from Munich by the name of Alfred Koppel managed to emigrate from Germany to the United States in the spring of 1941 with the help of a children’s assistance organization. His family was murdered in Kaunas. Koppel later collected the scattered reports about the murder of the Jews from the Munich area, and summarized them as follows (Wette, Jäger, page 128, quoting Al Koppel, Zuerst an der Reihe. Das Schicksal meiner Familie. Munich City Archive; translation):

Upon arrival at Kaunas the crowd of people coming from the station was chased up a hill, a long, long way on foot to one of the forts on the hill. […] Finally the one thousand people of the Munich transport, having reached the menacing Fort IX, were chased with blows and under threats into the cells in the fort’s cellars. […] They languished for three days in these horrible cells in the fort’s cellars. Then, on 25 November 1941, the prisoners were taken in groups of 50 to a pit in the area of Fort IX. My relatives were in one of these groups. […] When they arrived at the pit mother and Günther all of a sudden realized the whole dimension of the horror awaiting them. They saw the Sonderkommando squatting behind machine guns, ready to shoot them.[…]

Kaunas is the second largest city in Lithuania, with a population of more than 300,000.

Although mass killings of eastern European Jews had been going on for some time, this deportation of over 1,000 Breslau Jews to Kaunas marked the beginning of the policy of mass murder of the German Jews.

Stephanie was 46 years old when she was killed during the Holocaust on 29 Nov 1941 in Fort IX Kaunas, Lithuania

The above photos show the site at Kaunas Fort IX today. It’s now a museum and memorial.

Stephanie’s last known address in Breslau was 1b Tauentzienplatz, Breslau 5, Germany