My Grandfather, Georg Benjamin, was born in Breslau, Germany on 12th August 1894. His parents were Julius (Jacob) Benjamin and Julie Benjamin (born Sober). His birth certificate states his place of birth as Niue Odersrasse 8c, Breslau.

He worked as a window dresser and sign writer who also designed display fittings.

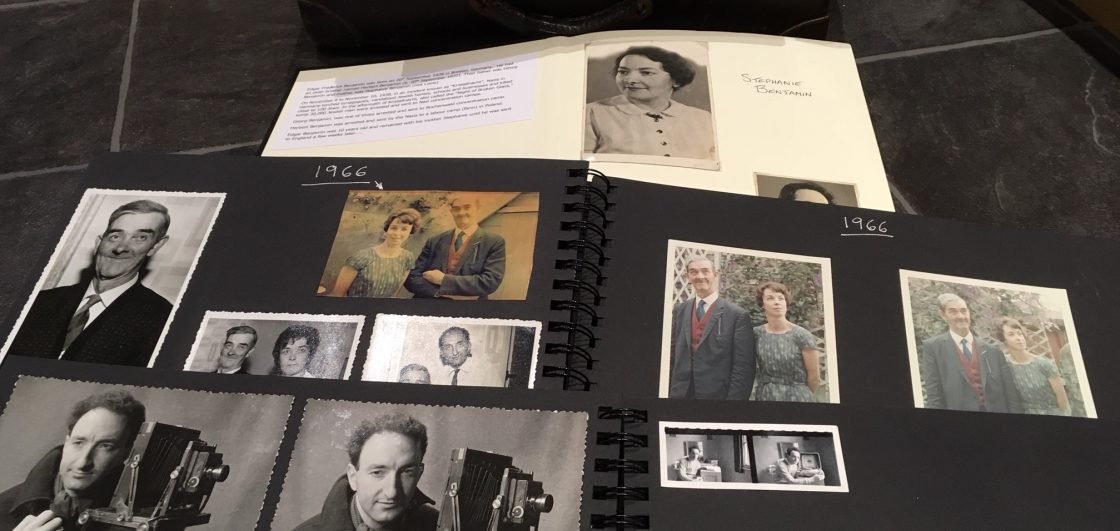

He married Stephanie Löw on 2nd March 1922 in Breslau, and later that year Stefanie gave birth to their first son, Herbert Siegesmund Benjamin on 20th September 1922. During this time, they lived at Friedrich Wilhelm Strasse 12, Breslau.

Six years later (to the day) Stephanie and Georg had their second son – Edgar Fritz Benjamin who was born on 20th September 1928 in Breslau, Germany.

They lived a happy life in Breslau, living close to their extended family but their happiness was short-lived.

The Nazi Rise to Power

In July 1932 Hitler made a speech in Breslau, attracting 16,000 listeners. In the following elections his party received 43% of the Breslau vote, the third-highest result in Germany. On 30th January 1933 he was appointed Chancellor of Germany.

It was not long before Jewish businessmen were forced to sell the fruit of their labours to “Aryans” (non-Jews) and attacks and harassment of Jewish professionals in Breslau were both horrific and routine. Nazism now made anti-Semitism socially acceptable in Germany. Jews had to surrender their passports so that their validity outside Germany was nullified. Jews were being blamed for inflation and even one newspaper claimed that “all our misfortunes are the fault of the Jews”.

The implementation of the Nuremberg laws in September 1935 meant that Jews became total outcasts of society. In November 1935 Jews were deprived of German citizenship and in 1938 were forbidden to drive and were required to return their licenses.

Many Jews throughout Germany sought to emigrate, although there was still a large proportion of German Jews who were determined to stay in their homeland and thought that this current wave of anti-Semitism would pass. As the years went on it became evident that this was not the case but it also became more difficult for families to emigrate.

Georg had fought for Germany during the first world war and had been awarded the Iron Cross for his bravery but this now counted for nothing.

The Breslau Jews maintained a stance of defiance and sought to persevere as a cohesive group with its own institutions. They categorically denied the Nazi claim that they were not genuine Germans, but at the same time they also refused to abandon their Jewish heritage. They created a new school for the children evicted from public schools, established a variety of new cultural institutions, placed new emphasis on religious observance, maintained the Jewish hospital against all odds and, perhaps most remarkably, increased the range of welfare services which were desperately needed as more and more of their number lost their livelihood. In short, the Jews of Breslau refused to abandon either their institutions or the values that they had nurtured for decades.

That was the heart of the problem of German Jewry: It was so much a part of German society that the Nazi blow hit it from within. Until 1938 many German Jews never thought of leaving Germany.

Kristallnacht

Between November 9th and November 10th 1938 an incident known as “Kristallnacht” (also called the “Night of Broken Glass”) took place across Germany.

German Jews had been subjected to repressive policies since 1933, when Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) became chancellor of Germany. However, prior to Kristallnacht, these Nazi policies had been primarily non-violent.

Nazi Party officials, members of the SA and the Hitler Youth carried out a wave of violent anti-Jewish pogroms throughout Germany. The rioters attacked Jewish residents and their homes. Jewish-owned shops and businesses were also plundered. They destroyed hundreds of synagogues, many of them burned in full view of firefighters and the German public and looted more than 7,000 Jewish-owned businesses and other commercial establishments. Jewish cemeteries were desecrated in many regions. Almost 100 Jewish residents in Germany lost their lives in the violence. In the following weeks the German government created new laws and decrees designed specifically to deprive Jews of their property and of their means of livelihood even as the intensification of government persecution sought to force Jews from public life and force their emigration from the country.

Thus, Kristallnacht figures as an essential turning point in Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews, which culminated in the Holocaust, the attempt to annihilate European Jews during the war.

Buchenwald Concentration Camp

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, some 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps. Georg was one of those arrested and was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp on 12th November 1938.

In the special camps set up by the SS in 1938 and 1939, the terror reached its most extreme form. The first of these camps were established after the anti- Jewish pogroms of November 9/10th 1938. In the days following the pogroms; by order of the Chief of the Security Police and the Security Service Reinhard Heydrich, the security police arrested some 30,000 Jewish males in Germany and deported 26,000 to concentration camps. This measure was intended as a means of forcing the Jews to relinquish their property and leave the country as quickly as possible. Between November 10th and 14th, 9,828 Jews were committed to Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

In total 9,845 Jewish people had been deported to Buchenwald during the wave of arrests that followed. Buchenwald Camp recently verified Georg’s imprisonment there. They confirmed that he was deported to the concentration camp on November 12th 1938 and that he was brought there with a transport coming from Breslau. Georg was registered with the prisoner number 28082. Upon their arrival at Buchenwald all Jewish victims of the November pogrom were placed in the “Special Pogrom Camp” on the west side of the roll call ground, a place where the terror of the SS reached its most extreme form.

Direct testimonies from victims of these arrests attest that these men were beaten and tortured from the moment of arrival in the camps. Around 30,000 Jewish men and boys were arrested over these few days and around two and a half thousand were killed or died over the following weeks and months.

By the end of the war, Buchenwald was the largest concentration camp in the German Reich. More than 56,000 died there as a result of torture, medical experiments and consumption. Members of the resistance formed an underground organisation in the camp in an effort to curb SS violence. The weakened inmates continued to die by the thousands right up until the camps liberation. When the Americans reached Buchenwald and its sub camps in April 1945, the supreme commander of the Allied Forces, Dwight D. Eisenhower, wrote: “Nothing has ever shocked me as much as that sight.”

Escape from Germany

During Georg’s imprisonment his wife Stephanie was desperately trying to find a route out of Germany for their youngest son Edgar who had just turned 10 years old.

Fortunately, a program called ‘Kindertransport’ was created.

The Kindertransport (Children Transport) started directly after Kristallnacht and was a process where children under 18 would be transported to safety in other countries. It was largely financed by the Refugee Children’s Movement and the Central British Fund for German Jewry. The aim was for them to be taken in by foster families or relatives until they could be returned to their parents at the end of the war. The majority of the children did not see their families again as they were victims of the Holocaust.

Stephanie applied for a place for Edgar on the Kindertransport and fortunately he left Germany on the first Kindertransport evacuation. The organisation generally favoured children whose emigration was urgent because their parents were in concentration camps or were no longer able to support them.

The first transport arrived three weeks after Kristallnacht in Harwich, Great Britain, on December 2nd 1938 with nearly 200 children on board.

On the same date that his son arrived in England, Georg was released from Buchenwald Concentration camp – he had not seen his son Edgar since his imprisonment in Buchenwald.

He was released on the condition that he made plans to leave Germany urgently and had to report to the police office regularly until his emigration was arranged. Jews had to queue for hours at Nazi offices, where they were subject to the whims of hostile officials. Georg had limited freedom of movement and was at risk of re-arrest; which would have meant almost certain death.

A copy of a revised birth certificate for Georg Benjamin was produced on 4th January 1939 after his release from Buchenwald. The middle name ‘Israel’ was added, which all Jewish men were obliged to add if their name was not deemed Jewish enough’ for easy identification

Kitchener Camp (Kent, England)

Georg was fortunate to be accepted at Kitchener Camp in England. One can only imagine how difficult it was for Georg to leave his wife Stephanie behind in Germany. He had the intention of getting her out to join him in England but he was unable to. Nobody could have predicted in advance when or if the War would begin and when he left Germany in July 1939, there would have only been weeks before war was declared on the 1st September and getting someone from Germany to England became even more difficult (probably impossible, except via indirect routes).

The creation of Kitchener Camp

The camp was created in early 1939 near Sandwich, Kent by influential Jews in England to house German, Austrian and Czech male refugees fleeing Nazi persecution.

The creation of the camp was crucial because so many Jewish men had been imprisoned in German concentration camps during November 2018.

Time was very much of the essence because many thousands remained imprisoned in appalling conditions in Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. They desperately needed a place of safety to which they could emigrate in order to obtain release from the camps.

The Home Office were rather uneasy regarding the suggestion of the establishment of transit camps in this country, as they feared that a pool of refugees might be formed in England. After further discussion it was decided that the principle of the establishment of transit camps be accepted, subject to the approval of the Home Office. The selection of the persons to be received in such transit camps would be in the hands of the Officials of the Reichsvertretung der Juden (Reich Representation of German Jews in Germany).

On being offered a means to leave the country – a condition of their release from the German camps – several thousand men gradually arrived at Kitchener camp throughout 1939. Although many of the men had injuries and ongoing poor health resulting from their incarceration, the hard physical labour required to refurbish Kitchener got underway immediately, despite the cold and muddy winter weather.

This work was carried out by the refugees themselves in the knowledge that for each hut made safe and habitable another 72 could be rescued.

Georg made it to Kitchener camp (via Dover) on 27th July 1939 aged 45. He was recorded as being present there in a Census dated 29th September 1939

When the men of Kitchener Camp left Germany, it is likely that they all had to leave loved ones behind. The men expected their families – parents, siblings, wives and children – to follow them to the UK. Some women were granted “domestic service visas” enabling them to escape the Nazis, but arrivals abruptly ended with the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939 and the Kitchener men must have known with heavy hearts that their chances of getting families out of ‘Greater Germany’ had now been closed off.

The exact number of men in Kitchener camp is unknown as many of the camp records were destroyed, however it is estimated the lives of around 4,000 men were saved. The records were destroyed in part to protect the men who had escaped to Britain and it was felt that their families would be at increased risk if the records fell into the wrong hands.

After war was declared in September 1939, a series of tribunals were held at Kitchener camp to determine whether the men were ‘friendly’ or ‘enemy’ Aliens. Those who arrived to conduct the tribunals already had a substantial amount of information about the men, to which they added over the course of these meetings. For many, it was the first opportunity they had had to share with those in authority what had happened to them in Germany. The men were not interned at Kitchener and they could request a pass to leave the camp meaning that Georg was able to request leave and visit his son Edgar regularly in Scotland.

Joining the British Army

The vast majority of the men in Kitchener camp were deemed ‘friendly’ and shortly afterwards they were given the opportunity to join the British Army as part of the Pioneer Corps. One Kitchener family reports that the men themselves demanded the right to be allowed to join up.

Kitchener camp became a Pioneer Corps training camp over the coming weeks and months following the start of the war.

Georg Benjamin joined the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps (AMPC) in Richborough on 5th January 1940. On 22nd November 1940, the name AMPC was changed to Pioneer Corps. They performed a wide variety of tasks in all theatres of war. The light engineering tasks of the Pioneer Corps included building anti-aircraft emplacements on the Home Front. Pioneers also carried stretchers, built airfields, repaired railways, and moved stores and supplies.

Hardly known today is the fact that many thousands of Germans and Austrians joined the Pioneer Corps to assist the Allied war efforts and liberation of their home countries. These were mainly Jews and political opponents of the Nazi Regime who had fled to Britain while it was still possible. The number of German-born Jews joining the British forces was exceptionally high. By the end of the war, one in seven Jewish refugees from Germany had joined the British forces. Their profound knowledge of the German language and customs proved to be very useful.

Now that Georg was a serving member of the British Army, he was able to request leave and continued to visit his son Edgar regularly in Scotland.

Georg was discharged from the Army on medical grounds on the 13th July 1943. His military conduct was described as “Very Good” and he had been declared unfit for any form of military service due to “Essential Hypertension”

Starting a new life…

When Georg left the army in 1943 he moved to Bonnybrigg in Scotland where Edgar was attending school and they moved in together. They first lived at Eldindean Road, Bonnybrigg and then in 1944, moved to 43 High Street, Bonnybrigg.

Georg had made attempts to discover the fate of his wife Stephanie but all reports from Germany indicated that she had perished during the holocaust.

On 1st October 1945 Georg and Edgar moved to 73 Heslington Road in York. Georg now turned his skills to designing and manufacturing new products (fancy goods). He called this new business ‘Steffana Studios’ named after his wife Stephanie who was now presumed dead following the war.

On 2nd November 1946, Georg married Herta Edith Benjamin who was a distant relative from Breslau. She had escaped to England in 1939 and had worked as a domestic help in Cheltenham. She lived with 2 or 3 different families and unfortunately was treated like a servant. Eventually she managed to get a job at the Cheltenham Theatre. After the war ended she met up with Georg in York.

Georg’s mother, Julie Benjamin (born Sober) also managed to escape Nazi Germany and fled to Argentina with her Daughter and Georg’s sister Else Shwarz. Julie died in Argentina in 1947.

In 1947 Georg and Edgar applied for British Nationality and on the application for Georg it stated:

He conducts a small wholesale business at his residence 73 Heslington Road, York, which includes the manufacture of novelty coat and towel hangers and the framing of pictures for which he holds British patent no.580470. He trades under the name “Steffana Studios”

Georg and Edgar received their Certificate of Naturalisation on 14th June 1947.

Georg suffered a stroke during the 1950’s which left him paralysed down his left side but he was still able to get around.

Georg died on 17th November 1959 in York Hospital after having a further stroke at home (73 Heslington Road, York). He is buried in Leeds UHC Cemetery, Gildersome, Leeds, UK.

The death certificate states Cause of Death as Coronary Artery Thrombosis due to atherosclerosis due to essential hypertension aggravated by services in HM Army in 1939-1945 war.